Cruise on over to this celebration of of...

Church marks 150 years ... and counting

Back in the day, your local church and the one-room schoolhouse that your children attended were focal points of society. And, as such, they wielded significant influence within the community.

That continues today, launching discussions on topics ranging from violence prevention to reproductive rights, bullying to homelessness, environmental stewardship to world hunger. And more often than not, the First Presbyterian Church in Harvard was in the thick of it – be it mission work abroad or women’s rights. In 1963, Jane Schultz Wolf and Lillian Booth were the first women to be ordained as elders at First Presbyterian Church – and the first in the Freeport Presbytery.

“It’s very much a part of who we are and how we believe Christians should live out their faith,” former First Presbyterian pastor the Rev. Jeff Borgerson said.

Interim pastor Claire Brennecka currently leads the flock of about 325 members.

Borgerson noted that theologian John Calvin instilled in the Presbyterian church a connection between religious faith and community that often manifests itself in activism.

“[England’s] King George called the American Revolution the Presbyterian insurrection,” he said.

On June 24, the congregation will mark the First Presbyterian Church of Harvard’s sesquicentennial. An “eventful” service is planned for

10 a.m., followed by an open house and luncheon from

11 a.m. to 2 p.m. For details, visit fpcharvard.org.

Mary Jane Haldeman, a church member for 68 years and its unofficial historian, said before women were afforded equal opportunities in the workplace, the church served as a creative and constructive outlet. In addition to the Presbyterian Ladies Society, which began shortly after the church formed, JU (which stands for Just Us) was formed in 1908 by a group of young ladies who had attended a Sunday school class taught by Mrs. B.F. Manley. Another young women’s group, TEL (which stands for Biblical characters Timothy, Eunice and Lois) was organized in 1947.

“That was your social gathering [opportunity] – the church and church functions. The women always put on turkey dinners, and women’s groups were always very active,” Haldeman said. “Today, nobody takes the time or makes the time anymore. Parents are busy running younger children from group to group.”

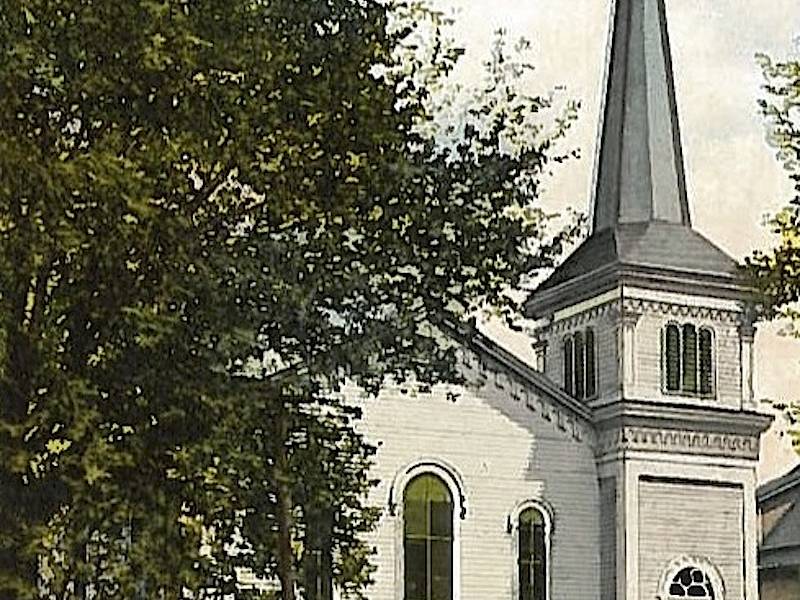

The First Presbyterian Church began with a meeting in February 1868 with two visiting clergy and seven newly signed members. But in a month they had organized a Sunday school, and within a few months, membership reached 37. By 1869, they had scraped together the $845 needed to secure a loan for the $3,714 needed to build a little white church at 309 N. Division St.

The new church included an auditorium, a kitchen and a row of carriage sheds in back. What it lacked was running water.

In the church’s centennial history book, Verne Palmer recalled fetching water from next door, where Dr. J.G. Maxon lived – first to make dinner, and later to clean up.

“For all this labor, he received his meal, for which he thinks the price was

25 cents,” former church historian Grace Stevenson wrote.

The first sanctuary also lacked comfortable seats, to the point where families started customizing cushions stuffed with cotton batting.

“However, it behooved people who made their own cushions to get to church right on time; otherwise their pew would already be taken or your cushion might have been taken from your pew and slipped onto another bare pew – leaving your pew hard and bare,” Stevenson wrote.

In 1906, the Rev. J.L. Tait arrived and became the first minister to wear a robe while he preached. It was during this time that the church launched its annual bazaar at the Harvard Opera House. The building later became the Cottage Hospital, and then the Harvard Retirement Home.

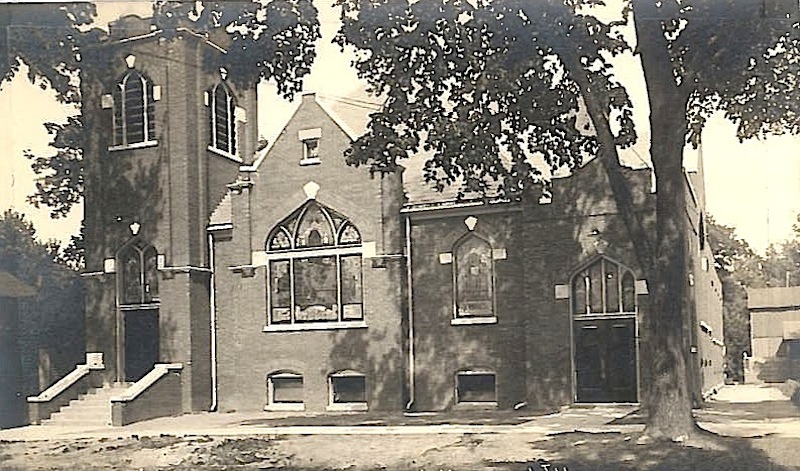

Construction of a larger church began in 1911 at the same location on Route 14. Completed in 1912 at a cost of $21,000, amenities included a hand-carved pulpit by Guy Hamlet, stained-glass windows and a $2,500 Votteler-Hitch organ – $875 of which was donated by business titan Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie and his family belonged to the Presbyterian Church in the U.S., but the steel magnate spent much of his life eschewing organized religion. When someone asked him why he donated money to more than 7,000 churches so they could buy organs, Carnegie replied, “I give money for church organs in the hope [that] the organ music will distract the congregation’s attention from the rest of the service.”

In the 1920s, the church had its own rifle team led by target instructor Ralph Marshall. Marshall, who owned Marshall’s Hardware on Ayer Street, supposedly allowed the boys to practice in the store’s basement, Haldeman said.

A church theater group, the Harpres Players, became popular in the 1930s. Its directors were Helen Heatley Ford and Sylvia VanAntwerp Crane. And in the early ’70s, the church sponsored The Cellar in the church basement. This meeting spot for Harvard youth later changed its name to the Coffee House.

On May 30, 1998, the church broke ground on its existing home at 7100 Harvard Hills Road. The 365 parishioners moved into the 17,000-square-foot facility on 10 acres in 1999 – a decade after Borgerson arrived from Hoopston with his wife, Joyce, and two sons. Borgerson, who moved to Antioch after retiring last May, is not at all surprised by the church’s resiliency. Teamwork is part of its DNA.

“Officers are elected. The church is very representational,” Borgerson said. “It’s also very member-driven. Committees are how we really operate, not as individuals. So it gives a lot of people an opportunity to get involved in things and be part of the decision-making. There is a lot of buy-in.”

• • •

Appeals to “lay that willow on that onion” have nothing to do with cooking or gardening. In this instance, “willow” refers to a “ base ball” bat, “onion, apple, horsehide or pill” refers to the ball … at least it did in 1860.

The McHenry County Historical Society and Grayslake Heritage Center will play their next Civil War-era baseball match at 2 p.m. Sunday at Village Hall Park in Prairie Grove off Barreville and Ames roads. The annual tilt pits the McHenry County “Independants” against the Grayslake Athletics.

This type of Civil War-era “base ball” differed radically from today’s rules. Players did not use gloves. A ball caught on the first bounce was considered an out, and a ball was ruled fair or foul based solely on where it first touched the ground.

• Kurt Begalka, former administrator of the McHenry County Historical Society & Museum.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.