Museum, Library & Office Closed

Pandemics of the past

With potentially months remaining in this year’s flu season, the 2017-18 outbreak could go down in history as one of the deadliest ever.

For the first time in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 13 years of monitoring influenza, every state in the continental U.S. is experiencing “widespread” virus activity that has resulted in the hospitalization of about 12,000 people and the deaths of an untold number – 53 of them children.

A spokeswoman for the CDC said the agency does not require the reporting of flu-related fatalities, so exact numbers are unlikely and a best-guess synopsis will not be forthcoming until the start of next year’s flu season. However, between 12,000 and 56,000 people die of influenza in a typical year.

Unfortunately, this is not a typical year. We are poised to surpass the 2014-15 flu season, in which 34 million Americans contracted the flu, 710,000 were hospitalized and about 56,000 died.

My intention is not to scare you into action, although frequent hand-washing and avoiding sick people is good advice.

Rather, let’s put all of this in historical perspective: We’ve seen this kind of thing before, and we’re going to see it again. We’re in an arms race with evil, mutating viruses. I was surprised to learn that the H3N2 flu virus is particularly deadly for those of us born before 1968, since our first exposure as children was to a different strain.

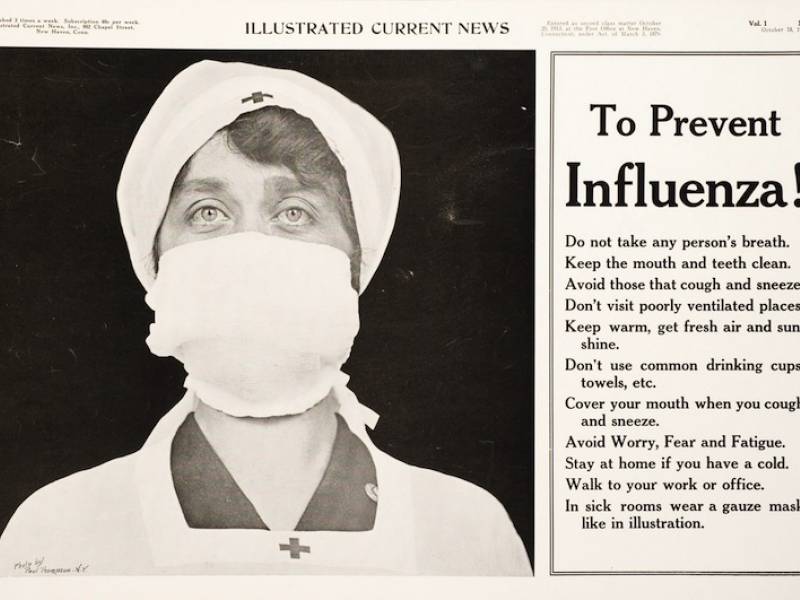

The good news is, like the old adage states, forewarned is forearmed. Unlike 1918, when a flu pandemic swept across the globe, infecting a half-million people and leaving an estimated 20 million to 50 million victims in its wake, doctors know the microscopic killer is not a type of bacteria, and they how to curtail its spread – provided that experts divine the right preventive cocktail before next flu season.

This year’s vaccine, regrettably, did not match well. Furthermore, the approach of growing vaccines in chicken eggs renders them less effective.

But the one thing that really should scare you is the current state of health care and its repercussions on potential future pandemics.

During the Spanish flu of 1918, a shortage of physicians and nurses because of World War I left inexperienced medical students to pick up the pieces.

Also, the scope of the problem quickly outstripped hospital capacity. More than 25 percent of the U.S. population became sick, meaning schools – even private homes – were pressed into service as makeshift hospitals.

Equally impactful was its effect on society. People were encouraged to avoid public places such as theaters and sporting events. Businesses, their employees sick or quarantined at home, were forced to close. Garbage remained on the curb and crops in the fields. Add zombies, and we could be talking about an episode of “The Walking Dead.”

The infection of many medical personnel, as well, created a perfect storm.

Only much later did researchers discover that the influenza virus had invaded the lungs of its victims and created conditions rife for bronchial pneumonia.

The History Channel website noted: “Victims died within hours or days of their symptoms appearing, their skin turning blue and their lungs filling with fluid that caused them to suffocate. In just one year, 1918, the average life expectancy in America plummeted by a dozen years.”

By summer 1919, the flu pandemic suddenly ended. It’s unknown exactly where the particular strain of influenza that caused the pandemic originated – although it was labeled the Spanish flu, since that country was among the first to be hit by the disease. We do know, however, that it spread quickly to nearly every country on the planet – and that was at a time when there were not the wholesale, mass transit options and huge event venues that exist today.

You could argue the opportunity for the spread of disease has never been greater.

Suzanne Hoban, executive director of the Family Health Partnership Clinic in Crystal Lake, said influenza cases remain a huge challenge for patients and staff alike.

“Half of our workforce is decimated,” she said. “We’re running on a skeleton crew right now. And all of these people got flu shots.”

That’s the thing about the influenza virus. It mutates.

“The flu that we have now could morph and not be the same flu in May,” Hoban said. “That is why having a universal flu strain vaccine is so difficult.”

Global warming has the potential of further raising those stakes by reactivating long-dormant bacteria and viruses trapped in the Arctic permafrost.

Recent reports in The Atlantic magazine and on National Public Radio shed light on a growing fear that “zombie pathogens” might be unleashed should their frozen victims thaw out.

But for now, there are more than enough parallels between today and the world a century ago to occupy our thoughts. A report by the National Institutes of Health noted:

“The onset of the influenza pandemic in the fall of 1918 occurred at a time when wartime dangers and dislocations had already slowed immigration to the United States. The total number of immigrants entering the U.S. had dropped to 110,618 in 1918 from 1,218,480 in 1914.”

In similar fashion, the current political climate has curtailed the influx of newcomers to this country – following a similar uptick in immigration at the turn of the century into the U.S. Ramifications include the reluctance of illegal immigrants to seek care for fear of being deported, as well as barriers to foreign-born medical students and doctors coming to our shores.

As many areas of the country have experienced firsthand already, as hospitals close and physicians retire, it could get harder and harder to find the care a person needs at a time when and where they need it. Not even rolling back out-of-control insurance premiums will help with that.

• • •

Buy your copy of the new Illinois bicentennial publication, “200 Objects That Made History in Lake & McHenry Counties.” The book is a collaborative effort of the Lake County Historical Alliance, which consists of 23 historical societies and history museums, including the McHenry County Historical Society & Museum in Union.

The book tells the story of Lake and McHenry counties by showcasing historical objects found in the eclectic collections of the alliance’s member institutions. Stunning photographs accompany these stories, which take readers on a unique historical journey.

“This is the perfect book for people who love to browse their way through history,” said Debbie Fandrei, book project manager and curator of the Raupp Museum in Buffalo Grove. “Each page features two different historical items – just enough to give readers a glimpse of the past, and all of the fascinating stories it contains.”

Copies of the soft-cover book are for sale in the McHenry County Historical Society & Museum store for $15, as well as online at blurb.com/b/8490907-200-objects-that-made-history-in-lake-and-mchenry.

• Kurt Begalka, former administrator of the McHenry County Historical Society & Museum in Union.

Published Feb. 5, 2018 in the Northwest Herald.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.