Museum, Library & Office Closed

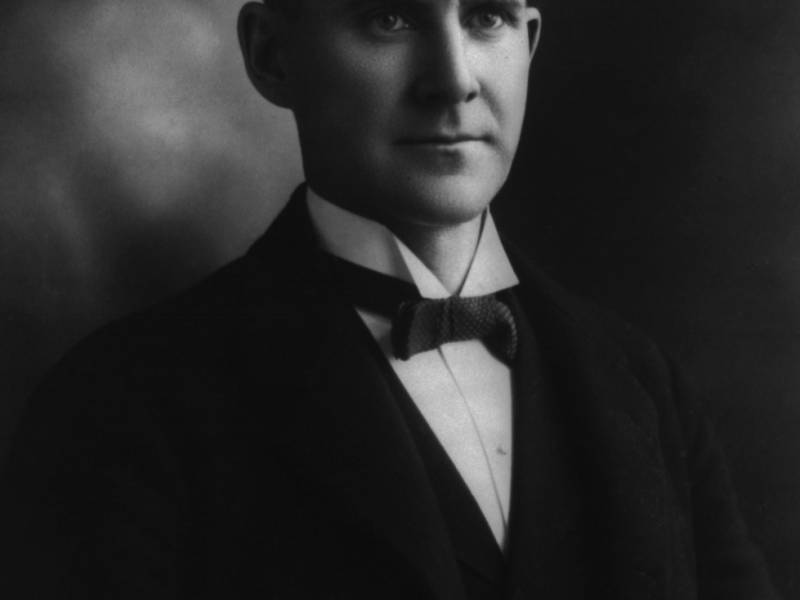

Eugene V. Debs' vision lives on in Bernie Sanders and McHenry County

On Nov. 22, 1895, Eugene V. Debs stepped out of the front door of the jail on the Woodstock Square a free man.

The McHenry County Historical Society’s Perkins Players will present an original drama marking that event at 7 p.m. Thursday, June 16, on the Square – starting outside the jail and moving over to the bandstand. Period clothing is encouraged, as are lawn chairs to sit on for this free event that will feature appearances by such notables as defense attorney Clarence Darrow, trailblazing journalist Nellie Bly and, of course, Debs.

A federal court sentenced the then-president of the American Railway Union to a six-month sentence. In his 1927 book, “Walls and Bars,” Debs wrote:

“With my associate officers of the American Railway Union, I was transferred to the McHenry County Jail, Woodstock, where I served a six months’ sentence in 1895 for contempt of court in connection with the federal proceedings that grew out of the Pullman Strike of 1894. My associates served three months, but my time was doubled because the federal judges considered me a dangerous man and a menace to society.”

The native of Terra Haute, Indiana, had gained fame among a large number of Americans by leading railroad workers on a job action affecting Pullman cars on passenger trains. He and members of the American Railway Union did this in sympathy with those who had gone on strike in 1894 against George Pullman and the Pullman Palace Car Co.

Local railroad historian Craig Pfannkuche said Pullman had cut wages at his massive factory, located at 111th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue in Chicago, but kept the rents and prices at the company store high during the recession of 1893. Striking workers asked Debs, as leader of the ARU, to help by refusing to handle Pullman’s famous sleeper cars. Their hope was keeping these cars out of service would force Pullman to the negotiating table, Pfannkuche said.

Debs approved of the action, but it was short-lived. Pullman convinced President Grover Cleveland to intervene against the ARU by sending in federal troops and forcing workers to handle Pullmans. This action was instrumental in breaking the strike.

Debs was found guilty of contempt, his attempt at a jury trial thwarted. In 1894, he was thrown into a Cook County Jail cell occupied by five other men. Debs later wrote that the jail was infested with “nameless vermin” and vicious sewer rats “nearly as big as cats” that made it difficult for one to put their feet on the stone floor.

“I recall a deputy jailer passing one day with a fox terrier. I asked him to please leave his dog in my cell for a little while so that the rat population might thereby be reduced,” Debs wrote. “He agreed and the dog was locked up with us, but not for long. For when two or three sewer rats appeared, the terrier let out such an appealing howl that the jailer came and saved him from being devoured.”

Debs decided then and there that he would do all in his power to help “those unfortunate souls” incarcerated there.

“I felt myself on the same human level with those Chicago prisoners,” Debs wrote in “Walls and Bars.” “I was not one whit better than they. I felt they had done the best they could with their physical and mental equipment to improve their lot in life, just as I had … .”

Fortunately for Debs, there were no short-term federal prisons. And, as New York World reporter Nellie Bly noted in a Jan. 20, 1895, jailhouse interview with Debs, the Chicago jail was overflowing with “guilty and innocent” prisoners.

“Unlike the street cars, it cannot squeeze in another one,” Bly wrote.

Upon his arrival at the Woodstock depot, the Daily Sentinel reported that McHenry County Sheriff George Eckert and “half the male population of the city” greeted Debs.

“The farmers in that vicinity did not relish the idea of my being boarded among them even as an inmate of their jail. They had been reading the daily newspaper and had concluded that I was too dangerous a criminal to be permitted to enter the county, and it was reported that they would gather in numbers at the station on my arrival and attempt to lynch me, or at least prevent me from disembarking,” Debs later wrote. “When we arrived at Woodstock, a number of them were at the station, but they had evidently been advised against carrying out their enthusiastic program for they made no hostile demonstration.”

In the months that followed, Debs traveled back and forth to Chicago with his attorney, Clarence Darrow, to deal with appeals related to his conviction. Darrow lost each appeal, and Debs was forced to serve out his sentence.

Concerning his release, the Sentinel begrudgingly reported that a group of more than 300 “crank leaders and others who were not cranks in the cause of the laboring man” waited for his release. “When Debs made his appearance they fairly went crazy with delight, rending the air with cheers and tiger shouts lifting [him] onto their shoulders that the crown might see him.”

The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, reported that “eight carloads of Debs’ friends had gone down to Woodstock to greet him on his release from jail and several thousand men were at the station of the North Western road when the train bearing Debs and his friends arrived.”

Debs was carried on the shoulders of four men from the train station to Central Music Hall, about a mile away, amid cheers and hat waving.

“Speaking for myself, personally, I am not certain whether this is an occasion for rejoicing or lamentation,” Debs told the crowd that evening. “I confess to a serious doubt as to whether this day marks my deliverance from bondage to freedom, or from freedom to bondage.

“Certain it is, in the light of recent judicial proceedings, that I stand in your presence stripped of my constitutional right as a free man and shorn of the most sacred prerogatives of American citizenship; and what is true of myself is true of every other citizen who has the temerity to protest against corporation rule or question the absolute sway of the money power.

“It is not law or the administration of law of which I complain. It is the fragrant violation of the Constitution, the total abrogation of the law, and that usurpation of judicial and despotic power, by virtue of which my colleagues and myself were committed to jail. …”

While in the McHenry County Jail, Debs grew increasingly cynical of capitalism and came to embrace the labor movement as class warfare. After announcing his conversion to socialism in 1897, Debs founded the Socialist Party of America and ran unsuccessfully as its presidential candidate five times – in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912 and 1920. Ironically, Debs was in an Atlanta prison the last time, serving a 10-year sentence for violating the Sedition Act. He was released by order of President Warren G. Harding on Christmas Day, 1921 – although without his citizenship restored.

He died of heart failure on Oct. 20, 1926, in Elmhurst. His cremated remains were returned to his birthplace and interred in the Highland Lawn Cemetery with only a simple marker.

“Standing here this morning, I recall my boyhood,” Debs told a Federal Court of Cleveland, Ohio, on Sept. 18, 1918. “At 14, I went to work in a railroad shop; at 16 I was firing a freight engine on a railroad. I remember all the hardships and privations of that earlier day, and from that time until now my heart has been with the working class. I could have been in Congress long ago. I have preferred to go to prison.

“I am thinking this morning of the men in the mills and the factories; of the men in the mines and on the railroads. I am thinking of the women who for a paltry wage are compelled to work out their barren lives; of the little children who in this system are robbed of their childhood and in their tender years are seized in the remorseless grasp of Mammon and forced into the industrial dungeons, there to feed the monster machines while they themselves are being starved and stunted, body and soul. I see them dwarfed and diseased and their little lives broken and blasted because in this high noon of Christian civilization money is still so much more important than the flesh and blood of childhood. In very truth gold is god today and rules with pitiless sway in the affairs of men.

“… I am opposing a social order in which it is possible for one man who does absolutely nothing that is useful to amass a fortune of hundreds of millions of dollars, while millions of men and women who work all the days of their lives secure barely enough for a wretched existence.

“This order of things cannot always endure. I have registered my protest against it. I recognize the feebleness of my effort, but, fortunately, I am not alone. There are multiplied thousands of others who, like myself, have come to realize that before we may truly enjoy the blessings of civilized life, we must reorganize society upon a mutual and cooperative basis; and to this end we have organized a great economic and political movement that spreads over the face of all the earth.”

It is a familiar message, a message we’ll no doubt hear a century hence and one we hear on a near daily basis today.

“Tonight, we served notice to the political and economic establishment of this country that the American people will not continue to accept a corrupt campaign finance system that is undermining American democracy, and we will not accept a rigged economy in which ordinary Americans work longer hours for lower wages, while almost all new income and wealth goes to the top 1 percent,” Sen. Bernie Sanders said after winning the New Hampshire Democratic primary in February.

“What the American people are saying – and, by the way, I hear this not just from progressives, but from conservatives and from moderates – is that we can no longer continue to have a campaign finance system in which Wall Street and the billionaire class are able to buy elections. Americans, no matter what their political view may be, understand that that is not what democracy is about. That is what oligarchy is about, and we will not allow that to continue.”

• Kurt Begalka, former administrator of the McHenry County Historical Society & Museum.

Published: Monday, June 6, 2016 in the Northwest Herald

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.