For some time now we’ve been contemplating writing a series of focused articles on very specific subjects – the kind of things school children rarely read about in their history text books.

The writings will be made available in paper form as well. Called “The Before… Series.” We are concentrating on the decade of the 1920’s – a time of great change, social upheaval, easy credit, hard roads, electricity, radios, golf.

Yet it was also a time when most McHenry County residents still live on family farms, attended one-room schools and remembered the so-called “Good Old Days.”

In 1917, as the United States slid to war with Germany, a group of women approached the White House in Washington, D. C. They stood quietly at the home of President Wilson. The banners that they wore draped from shoulder to waist proclaimed them to be “Silent Sentinels;” women who wanted the President and Congress to take action to give all American women of age the right to vote in all elections. Members of this group stood continuous vigil until after the Congress accepted Wilson’s proposal to allow the states to ratify the 19th amendment. On June 10, 1919, Illinois became the very first state to vote in favor of that ratification.

Surprisingly, especially considering all that has been said, much of it greatly romanticized, about the “ratification struggle,” McHenry County newspapers took almost no notice at all of that ratification. The truth of the matter is that McHenry County women were, since 1913, free to vote in township and municipal elections. Women in many trans Mississippian states held the right to vote in local and state elections, in some cases, as early as the 1890’s. This early exercise of the local franchise by women as well as the November 1917 mobilization of women in the nation to do important war work made county, state, and national woman’s suffrage almost a foregone conclusion at the end of World War I.

Surprisingly, especially considering all that has been said, much of it greatly romanticized, about the “ratification struggle,” McHenry County newspapers took almost no notice at all of that ratification. The truth of the matter is that McHenry County women were, since 1913, free to vote in township and municipal elections. Women in many trans Mississippian states held the right to vote in local and state elections, in some cases, as early as the 1890’s. This early exercise of the local franchise by women as well as the November 1917 mobilization of women in the nation to do important war work made county, state, and national woman’s suffrage almost a foregone conclusion at the end of World War I.

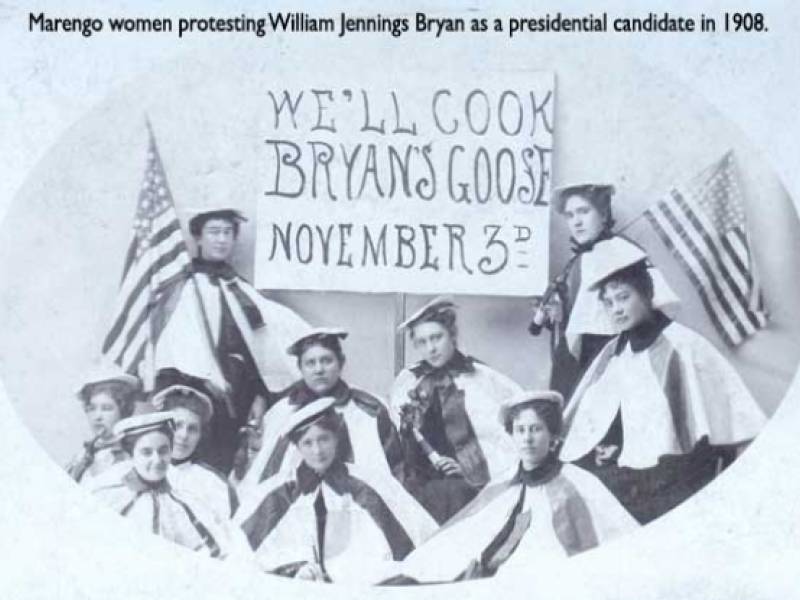

The Illinois local woman’s suffrage struggle which culminated in 1913 can not correctly be described neatly and cleanly only in terms of whether women had the right to vote. The story deeply involves the various county chapters of the Illinois “Anti-Saloon League” and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). In McHenry County, both groups had extremely active chapters led by women of great note in the county. Hand in hand with these groups was a political movement called “Progressivism” which was sweeping the nation in the first decade of the 20th century. Progressives, like Theodore Roosevelt who ran for the Presidency in 1912 as a “Progressive,” believed that the nation could be a better place if a variety of social reforms were accomplished through national, state, and local legislation. It was believed that an important key to this legislation was women who were, at that time, believed to be the best and highest holders of social morals. Progressives believed that if women were to be allowed to exercise the franchise they would surely vote in favor of “progressive” educational, justice, and environmental reforms.

A classic example of “progressive womanhood” in McHenry County was Marengo’s Elizabeth Sisson Shurtleff, the wife of Edward D. Shurtleff who happened to be, between 1901 and 1910, the powerful Speaker of the House of the Illinois General Assembly. Active in both the McHenry County chapters of the Anti-Saloon League and the WCTU, Elizabeth Shurtleff believed strongly that if the widespread use and sale of alcoholic beverages could be contained, even eliminated, families would become more stable, children would be happier, and public education would flourish. Her husband supported her in her beliefs and activities.

In 1915 in “Progressive” fashion, Shurtleff worked with the noted Jane Addams to introduce a bill in the Illinois House to ban the employment of children under the age of 16 (with certain exceptions) in Illinois. Although Edward Shurtleff had given up the Speakership in 1910 because of his alleged involvement in the bribery scandal which forced William Lorimer to resign his US Senate seat (Chicago newspapers called Shurtleff a “bag man” for Lorimer), he was able to retain both the trust of his community’s residents and his seat as a state representative.

Those who saw the saloon (aka – neighborhood tavern) as being necessary to the happiness and contentment of the average working man went to great lengths to convince newspaper readers and any others who would listen that “Woman’s suffrage will double the irresponsible vote. It is a menace to the home, men’s employment, and to all business.”

The Anti-Saloon League believed that if women were allowed to vote, their votes would go far to implement programs bringing excessive drinking to an end and, thus, bringing about improved home and community environments.

In May of 1913, the Illinois Senate, under the sponsorship of Republican turned Progressive, Hugh S. Magill, passed a bill to allow women to vote in township and community elections by a vote of 29 to 15. This action raised the ire of Democrat Anton Cermack of Chicago, who would later become the mayor of Chicago (and vacationed often in Fox River Grove), who was pushing a variety of legislative initiatives catering to the needs of the state’s saloon and tavern owners. Cermack believed that Shurtleff would, regardless of the appeals of Shurtleff’s wife, support his pro-saloon stance, especially since Hugh Magill was the very man who had led the charge against Lorimer going to the United States Senate.

The leadership of the Anti-Saloon League responded to Cermack’s actions in the House by appointing, based on the recommendations of the lady leaders of the WCTU, a number of floor captains in support of the suffrage bill. One such floor captain was, at the quiet insistence of Elizabeth Shurtleff, her husband, Edward. The WOODSTOCK SENTINEL reported (June 12, 1913, page 1) that, as the time for the vote on the bill arrived on June 11 “None of the former Speaker’s close friends dreamed for a moment that he would vote for the woman’s bill.” The CHICAGO INTER-OCEAN reported (June 12, 1913) that the passage of the bill was questionable when Edward Shurtleff asked to speak. The MARENGO REPUBLICAN, Shurtleff’s home town newspaper stated (June 13, 1913, page 4) that “Shurtleff made a speech that electrified the members and snatched the suffrage bill from [failing] at that critical moment.” As reported in the INTER-OCEAN, Shurtleff said

For five months we have witnessed the spectacle of a moving picture show over this state at which fallen women were exploited for the edification of our citizens. That spectacle has brought me to the opinion that if that is the best men can do in legislative halls, then it is high time that we took the women into our councils and turned over to them the work of rescue. That is a woman’s work and I am now ready to put aside my prejudices and hand over to the women of Illinois the right to say what shall be done in matters of this kind. Mr. Speaker, I vote “Aye!” on this bill.

Shurtleff’s vote on the measure was enough to convince those friends and allies he had made in the House while he was its Speaker, to bring 83 votes in support of the measure, 6 more than were necessary for passage.

The WOODSTOCK SENTINEL published a report (June 13, 1913) that shortly before the passage of the Illinois suffrage bill the noted English suffragette, Emily Pankhurst, visited Woodstock and participated in a Suffrage Rights parade around the Square with members of the Oliver Typewriter “repair, experimental, and power departments.” The columnist vacuously reported that the

… winsome Emily, gowned in one of Gay Paree’s latest creations headed a parade up Main Street, around the square and down Benton Street to the ardent Emily’s headquarters at the Oliver Typewriter plant [followed by] tube skirt, sheath skirt, overdrape, underdrape, tunic and Balkan blouse to say nothing of the divided skirt which received undivided attention.

The paper had nothing to say about the right to vote granted to women. Similar to other McHenry County newspapers, the HARVARD HERALD of June 26, 1913 printed a long article describing those offices for which women could vote. They were municipal and township offices only. The article stated that

Illinois enjoys the distinction of being the first large state in the union to grant women limited suffrage and the first state east of the Mississippi River to give women the vote privilege, though the ladies will not be vested with power to vote for every elective office because this can not be granted until the federal constitution is amended.

The McHENRY PLAINDEALER reported in its March 19, 1914 edition that the annual McHenry Township election would actually have a contest for one of the three offices, that of Township Collector. Not only would there be a rare contest for a position but the contest was between a man and a woman. The paper reported that “The present incumbent [John Niesen] is a man with many friends [and] has held the office for a number of terms.” Niesen’s opponent was Mrs. Mayme Harrison. The reporter then editorialized that

We believe that both candidates are well worthy and ably qualified to fulfill the duties of the said office. This places the voters in a rather difficult position as both candidates have no other means of support and it will be hard to choose between the two.

The PLAINDEALER reported the results of the contest in its March 26, 1914 issue. The reporter wrote

We have heard it said that the women of McHenry, when it came to voting time, would not go to the polls, but from the showing made last Saturday we may rest assured that the fair voters of this town and village can take care of their political duties just as well as the men and we see where the women will interest themselves more and more as years go on and we predict that it will not be long before they have politics well in hand.

The results of the election were 272 votes for Mayme Harrison and 447 votes for John Niesen.

The CRYSTAL LAKE HERALD of April 16, 1914 reported that Nettie Teckler was the first woman to cast a ballot in that community.

In sum, when the issue of national woman’s suffrage came before President Wilson in 1918, the issue had already been decided in McHenry County. Women were already showing considerable political strength by voting in appreciable numbers in those elections were they could. They had already proven themselves when the 19th Amendment was passed. The prognostication of the reporter of the McHENRY PLAINDEALER as to the role of women in American politics was vindicated.