For some time now we’ve been contemplating writing a series of focused articles on very specific subjects – the kind of things school children rarely read about in their history text books.

The writings will be made available in paper form as well. Called “The Before… Series.” We are concentrating on the decade of the 1920’s – a time of great change, social upheaval, easy credit, hard roads, electricity, radios, golf.

Yet it was also a time when most McHenry County residents still live on family farms, attended one-room schools and remembered the so-called “Good Old Days.”

It didn’t take long for the public to take to motoring. The automobile quickly left the realm of rich man’s toy to transportation necessity once Henry Ford made his Model T cheap and available. Folks liked taking to the open road despite the terrible conditions before the hard roads movement. Driving one’s car, a traveler wasn’t tied to strict railroad schedules and dress codes and mealtimes set up at railroad hotels. That sense of freedom, the excitement of travel adventure, and automobile road improvements created a tourism industry that continues today.

Those first automobile tourists traveled with everything, including the kitchen sink. Their car was a home-away-from home because these were the days before motels. Called tin can campers, auto gypsies, and auto campers, these earlier adventurers loved gadgets and regularly traveled with gasoline stoves, Dutch ovens, portable refrigerators, steam irons, wash tubs, big tents, folding beds, collapsible camp furniture, food, clothing, and sporting gear. Top heavy with equipment for all occasions, auto campers drove until tired, pulled off to the side of the road, and set up camp. The fact that a campsite might also be private property didn’t enter into the equation. As the numbers of these travelers increased, so did litter, damage to crops, theft of property, and general displeasure from those whose property was being violated.

In 1916 motorists averaged 125 miles a day. As roads improved, the mileage increased to 170 miles in 1920, 200 miles in 1925, and 300 miles in 1931. In McHenry County, Illinois, the 1920s saw its first organized efforts to formalize camping sites and lure the motoring public to places like Hebron, Richmond, Crystal lake, Spring Grove, Woodstock, McHenry, Marengo, and even little Solon Mills by providing tourist camps.

By 1921 it was estimated that 20,000 Americans drove cross-country compared to only 12 in 1912. That same year an estimated nine million Americans planned to go motor camping in the summer. I

As the number of auto campers continued to climb, so did the efforts on behalf of local businessmen organizations to capitalize on the trade these potential customers could provide to local businesses if only they could be lured into America’s small towns. It was argued that by setting up tourist camps, travel by automobile would be encouraged, and travelers would spend money on gas and oil, food, supplies, and souvenirs.

In September 1921, the Illinois Auto Club erected motorist guide signs through McHenry. It was shortly after that auto camps began springing up across the county. The first mention of one was in Woodstock in the summer of 1922. With the city providing the lights, sand, and water, the commercial club, comprised of city businessmen, agreed to build a shelter. The site chosen for the camp was called Standpipe Park, located at the intersection of Hill and JacNo records indicate how popular a stopping place this was; however, because of a nearby pond that has since been drained, it was often called “Skeeter” Park.

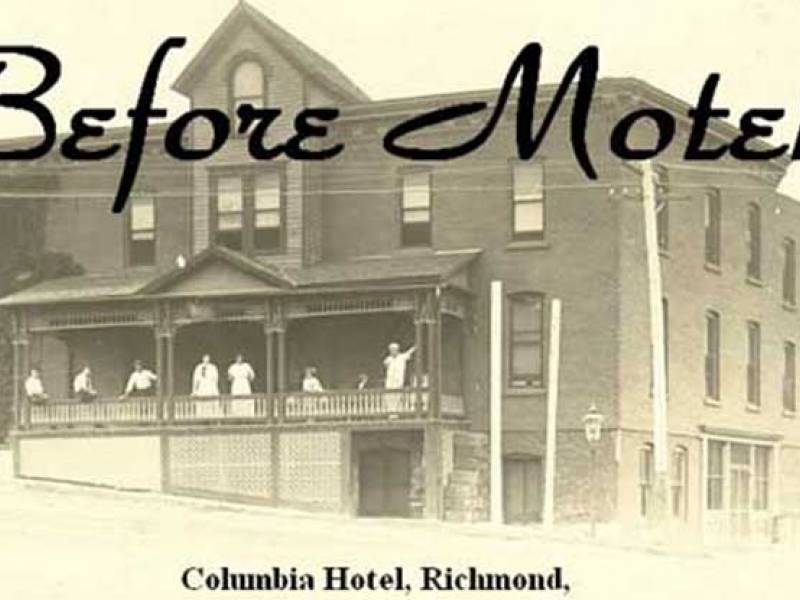

The following year the McHenry Plaindealer newspaper reported that a two-acre tract along the Nippersink Creek and near the Village of Richmond was to be set aside for a motor tourist camp. In short order, electric lights and a well were installed. The Osborn Tourist Camp, a private camp according to Robert Gardner of Solon Mills, was located in a grove of trees on West Solon Road off Route 31 and south of Richmond. The camp was still operating in 1927, but no one remembers how long it remained.

Meanwhile, McHenry was planning its own campsite. In late May 1923, N.H. Petesh and William Spencer of the McHenry Community Club contracted M.A. Conway about a tract of land east of the Fox River for tourist camping. Conway’s Woods (located on Lincoln Road), as the site was commonly called, had previously been used as a picnic ground. The Club struck a deal with Conway to rent a strip of land for their camp. They planned to erect a big sign above the entrance. The businessmen were worried they might lose the tourist trade without such a camp. Additional newspaper accounts indicated the site was gradually becoming known by the traveling public enough that Mr. Conway was trying to get park seats. By 1925 new signs were needed for Conway’s Woods and several businesses stepped forward to help. Alexander Lumber Company would donate the wood for one sign. Thomas P. Bolger would donate sign paint, and Mayor Wattles asked the City Council to approve two more welcome signs leading into the city, bringing the number up to seven.

It seemed that no community wanted to miss an opportunity to cash in on sales revenues generated by the traveling public. In Crystal Lake alone in 1924, there were 520 registered automobile owners.

Small towns like Hebron began agitating for a free tourist camp near their village. Spring Grove provided one, probably somewhere along today’s Route 12. Whether Hebron’s was ever established is unknown, nor do we know where the Spring Grove tourist camp was.

Over on the southwestern side of McHenry County, Marengo, one of the area’s oldest cities, sits right along one of the state’s oldest roads – Grant Highway or U.S. Route 20. In 1924 the Marengo City Improvement Association contacted Earl Penny to lease some of his land on Rowland Avenue for a tourist camp.

Earl’s daughter Gladys Penney shared her recollections about that camp in 1999 in the Society’s newsletter, The Tracer. According to Gladys, her folks had a farm at the end of Rowland Avenue just off Route 20, five blocks west of the downtown business district. A big sign on the highway directed motorists to the camp. Families drove in, pitched tents, and stayed overnight. She remembered them coming up to the farm just west of the camp to use the outhouse behind the big house, to get water from the well, and sometimes buy eggs, milk, or vegetables. After a year of operation, the Marengo Civic Improvement Association improved the camp with adequate toilet facilities for men and women. They also provided a new table and a new platform around the well. Around the same time, a 50¢ fee was imposed to help with the upkeep. According to a 1927 newspaper article, the auto camp was still operating.

As time went on, improvements were made to the motor camps. Travelers compared camps in one town and another and pressured for improvements, resulting in overnight usage fees. Crystal Lake, by 1925 was collecting a $1.00 parking fee for out-of-towners who parked at the lakefront.

The auto camps greatly appealed to the traveling public, especially women. The well-equipped camp could supply items a traveler wouldn’t need to pack himself, like picnic tables, tent floors, recreational equipment, and personal supplies. Besides, they offered clean privies, showers, and rain shelters.

Unfortunately, municipal-supported auto camps fell out of favor during the same decade, the 1920s, when they first flourished. Local newspapers like the McHenry Plaindealer excitedly announced every improvement when the campsites were new. But a lot was going on then. In 1922 alone, St. Patrick’s Parish in McHenry built a new church, a four-year new high school was approved, the McHenry Country Club opened the first nine of its 18-hole golf course, cement road building was moving ever closer, a sewer system was undertaken, and McHenry passed from a village to a city.

Tremendous growth and new technology brought about by access to electrical power and more leisure time affected McHenry County just as it did the rest of the country. As long as motor camps were new, they were news. Yet it was costly to stay competitive. In addition, as time went on, a different class of travelers showed up at the camps. These individuals took to the road and lived from one motor camp to another, looking for jobs and cheap lodging. They were not likely to spend as much in town as hoped for. Thus the shift to for-profit private camps, which were less conflicted in their mission. As one source (Americans on the Road – From Auto Camp to Motel, 1910-1945 by Warren James Belasco, 1979) put it, “Private operators of tourist camps weren’t torn at all. They targeted the spending tourist with more attractive camping facilities and, from there, cottages.” Municipal efforts failed because they were caught between serving the public interests of outdoor recreation or serving the profit interests of local merchants. A poll of 59 cities taken in 1930, for example, found that 29 had abandoned their camps because of private competition. This was happening inside McHenry County too.

The story of McHenry County’s auto camps ends with much less fanfare than when they began. It wasn’t much of a leap from tent sites to cottages in the tourist industry. To see that next step, a quick stop at the McHenry County Historical Society museum in Union will produce one of the 1949 – 1950 Orsolini Cabins, once located on Whiskey Corners (Routes 31 and 12 south of Richmond). Until the bigger owned chain motels replaced them, these little “Mom and Pop” owned cottages like Orsolini’s or McClure’s in Harvard served the traveling public in McHenry County just fine. Their story, however, is another chapter in American tourism history.

by…Nancy J. Fike